Blog

Hundreds of thousands of Americans with mild cognitive impairment are undiagnosed, studies find

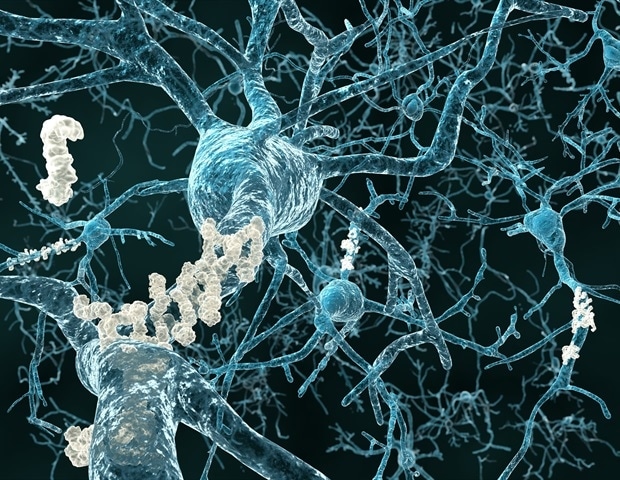

For many individuals, forgetting your keys or struggling to plan tasks can seem to be a standard a part of the aging process. But those lapses can actually be symptoms of something more serious: mild cognitive impairment, or MCI, which could possibly be an early sign of Alzheimer’s disease.

Unfortunately, most individuals who’ve MCI don’t realize it, so that they’re unable to make the most of preventive measures or latest treatments, corresponding to a recently approved drug for Alzheimer’s disease, that would slow its progression. Those are the findings of two latest studies published in parallel by researchers on the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

In a single study, published in Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, the researchers analyzed data from 40 million Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older and compared the proportion diagnosed with the speed expected on this age group. They found that fewer than 8% of expected cases were actually diagnosed. In other words, of the 8 million individuals predicted to have MCI based on their demographic profile, which incorporates age and gender, about 7.4 million were undiagnosed.

“This study is supposed to boost awareness of the issue,” says Soeren Mattke, director of the Brain Health Observatory at USC Dornsife’s Center for Economic and Social Research, who led the investigations. “We would like to say, ‘Listen to early changes in cognition, and tell your doctor about them. Ask for an evaluation.’ We would like to succeed in physicians to say, ‘There is a measurable difference between aging and pathologic cognitive decline, and detecting the latter early might discover those patients who would profit from recently approved Alzheimer’s treatments.

The prevalence of MCI is influenced by socioeconomic and clinical aspects. Individuals with heart problems, diabetes, hypertension and other health issues are at higher risk of cognitive decline including dementia. These health issues are more prevalent amongst members of historically disadvantaged groups, including those with less education and Black and Hispanic Americans.

The researchers found that detection of MCI was even poorer in those groups. Mattke says that is concerning because the general disease burden in those populations is higher. “So, they’re hit twice: They’ve higher risk and yet lower detection rates.”

The second study, published in Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease checked out 200,000 individual primary care clinicians and located that 99% of them underdiagnosed MCI. “There’s really only a tiny fraction of physicians ready to diagnose MCI who would find these cases early enough for optimum therapeutic potential,” Mattke explains.

MCI by definition doesn’t cause disability, whereas dementia is itself a disabling condition reflecting more serious cognitive impairment. In MCI, challenges to on a regular basis functioning are likely to be more sporadic, says Soo Borson, clinical professor of family medicine at Keck School of Medicine of USC and co-lead of the BOLD Center on Early Detection of Dementia, who was not involved within the studies.

MCI can are available various forms: forgetfulness is probably the most familiar form, Borson says. One other is an executive form, which mainly affects efficiency in getting things done and difficulty with tasks that was easier, corresponding to balancing a checkbook or paying bills online. There’s even a behavioral form -; through which mild changes in personality may predominate. These various forms often coexist.

It can be crucial to know that MCI refers to a level of cognitive functioning and never a particular disease state. Recent advances within the treatment of probably the most common reason for MCI -; Alzheimer’s disease -; lend latest urgency to improving detection of MCI.

There are several reasons MCI may be so widely underdiagnosed in america. A person is probably not aware of or bring up their concern; a physician may not notice subtle signs of difficulty; or a clinician might notice but not appropriately enter the diagnostic code in a patient’s medical record.

One other essential reason: Time during a clinical visit is probably not put aside to debate or assess brain health unless the visit was planned expressly to incorporate it. Detection of cognitive impairment will not be difficult, but it surely doesn’t occur without planning.

Mattke notes that risk-based MCI detection -; focusing attention on people at best risk -; would help discover more cases because time and resources could possibly be focused on those high-risk individuals. Digital tests that could possibly be administered before a medical visit could also help more people study their cognitive risk and current functioning.

Early treatment is significant, says Mattke, since the brain is restricted in its ability to get better -; brain cells, once lost, don’t grow back, and any damage can not be repaired.

For MCI brought on by Alzheimer’s disease, the sooner you treat the higher your outcomes. This implies though the disease could also be slowly progressing, each day counts.”

Soeren Mattke, Director of the Brain Health Observatory at USC Dornsife’s Center for Economic and Social Research

Source:

Journal reference:

Liu, Y., et al. (2023) Detection Rates of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Primary Take care of america Medicare Population. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2023.131.