Blog

Ultimate List of Git Commands

Anyone who uses Git, or has even seen it for that matter, knows there are a lot of terms and modifiers to maintain up with.

And sustain, it’s essential to, because it’s turn into the usual in version control for tech products today.

But as a substitute of just expecting you to maintain it all in your head, we put together this go-to resource filled with critical commands so that you can reference so you should utilize Git each effectively and efficiently.

Not a Git super user (yet)? That’s perfectly high-quality.

The commands we’ll detail here range from the on a regular basis to the more rare and complicated. And, as an added bonus, each is joined by tips about ways you should utilize it during a development project.

We’ll kick things off with some info on Git’s background, then wrap up with a full walkthrough of how you may use Git in a real-life setting.

Quick Debrief: Understanding Git, GitHub, & Version Control

Git is what its builders call a Source Code Management (SCM) platform. In other words, it’s a version control system. One which’s free, easy to make use of, and thus on the core of many well-known projects.

Which brings us to a logical query in the event you aren’t immersed on this planet of development: What exactly is version control?

Constructing something from code continuously takes a variety of trial, error, and steps. And, in lots of cases, collaboration.

It’s easy for essential elements that took a variety of effort to get overwritten or lost. For instance, in the event you’ve ever worked with a colleague in a live Google Doc, you understand what we mean.

A version control tool principally saves each iteration of your progress throughout a project. This is useful in case you must rewind to a previous version to review and grab certain elements to reuse — and even restore an older version if something in the present construct isn’t working as intended.

Git is installed locally, meaning it exists in your computer as a substitute of within the cloud. In truth, you don’t even need to be connected to the web when using it!

In this manner, it provides a secure repository (often called a “repo,” which is a space for storing for code) for a developer to save lots of every “draft” of a project they’re working on.

Git takes this one step further with the branching model for which it has turn into known.

With Git, a developer can create various code “branches” that reach from a project. These branches are principally copies of the most important project, which was called the “master” project, but that term is being phased out.

Changes in branches don’t impact the code of the most important project unless you tell them to. With branching, developers can do things like experiment with latest features or fix bugs. The changes made in a branch won’t impact the most important code unless you do something called “merging.”

Git makes perfect sense for website owners or developers working on their very own projects. But what about when you have to work with a team on a coding project?

Meet GitHub.

GitHub is a development platform for hosting Git repositories.

In other words, it’s the way you get your Git repos off of your local machine and onto the web, often for the aim of enabling people to collaborate on them.

GitHub is cloud based and for profit, though the fundamentals could be used without cost if you enroll.

The first function of GibHub is enabling developers to work together on a singular project in real time, remotely making code revisions, reviewing one another’s work, and updating the most important project.

GitHub maintains the core feature of Git: stopping overwriting and maintaining each saved version of a project. It also layers in every kind of additional features and add-ons like increased storage, fast development environments, AI-powered code writing, code auditing support, and rather more. (We recommend trying out the pricing page to see all the pieces on offer.)

It’s essential to notice that GitHub isn’t the one service on this space. Alternatives include Bitbucket, GitLab, etc.

Nonetheless, Git and GitHub after all work together like peanut butter and jelly, as you’ll see just a little later in this text.

First things first: an entire list of all of the Git commands developers and tech teams must be acquainted with to search out success on this version control environment.

21 Of The Most-Used Git Commands You Should Know

Are you ready for the last word Git cheat sheet?

On this section we’ll dive into the Git commands, instructions, principally, that you have to know to make use of Git successfully. And, we’ll even throw on some tips about how it’s possible you’ll use each of them in a project.

Pro tip for profiting from this document: Press “command + F” on a Mac or “Ctrl + F” on Windows to open a search box to search out a selected command, in the event you’re in search of something particularly.

git config

git config is a helpful command for customizing how Git works on three levels: the operating system level (system), user-specific level (global), and repository-specific level (local).

Check out git config with these moves:

git config --global user.email [your email]

This can be a command many devs run right after downloading Git to establish their email address.

git config --global user.name [your name]

For establishing your user name.

git config --local

Customize your local repository-specific settings. This can override default Git configs on the system and global levels.

Get Content Delivered Straight to Your Inbox

Subscribe to our blog and receive great content similar to this delivered straight to your inbox.

git pull

git pull is your command for fetching code from a distant repo and downloading it to your local repo, which can then be updated to match what you only pulled.

This act of merging is foundational to using Git. And, it’s actually “shorthand” for 2 other commands: git fetch then git merge.

Listed below are a couple of ways this command is often used:

git pull [remote]

Fetch a selected distant repo and merge it with the local you’re working on.

git pull --no-commit [remote]

This command still fetches the distant repo, but doesn’t routinely merge it.

Since pull is such a core Git command, there are tons of how to make use of it. This guide to Git Branch Commands offers much more examples and a few fresh combos you’ll be able to try.

git fetch

git fetch as a standalone command downloads commits from distant repos into local repos. It gives you the prospect to see and modify code from other devs.

Let’s check out this command:

git fetch origin

Downloads a duplicate of the origin distant repository and saves it locally. Nothing is modified or merged, unlike what git pull does by default.

git fetch --all

Grab data from all distant repos (origin included).

git fetch --shallow-exclude=[revision]

Excludes commits from a selected branch or tag.

git merge

The git merge command combines branches (most frequently two, but could be more) to create a singular history. Git will highlight conflicts that arise within the merge to be fixed.

Options for this command include:

git merge [branch name]

Use this to merge changes from the named branch into the branch you’re using.

git merge --abort

Stop the merge and restore the project to its pre-merge state. This command perfectly illustrates how Git helps maintain older code versions to guard project progress.

git add

git add is the command to make use of if you’re able to “save” a duplicate of your work. It’s fairly often used along side the subsequent command — git commit — as this adds (aka “commits”) what’s been saved to the project’s running history.

Listed below are some ways you’ll be able to specify what to save lots of (or “stage”) with this command:

git add [file]

This tees up all of the changes you’ve made to a selected file so it will probably be included in the subsequent commit.

git add [directory]

Much like above, this cues changes to a selected directory so it’s ready for the commit.

git commit

git commit is the second command within the trifecta of creating and tracking a change in Git.

This command principally says to store any changes that were made with the git add command. To not make the changes to the most important code, simply to hold them safely.

Some options for using this command include:

git commit --amend

Modifies the last commit as a substitute of making an entire latest one.

git commit -m [your message here]

Annotate your commit with a message, which matches contained in the brackets.

git push

git push completes the collaboration cycle in Git. It sends any committed changes from local to distant repositories. From here, other developers on the project can start working with the updates. It’s the alternative of the fetch command.

Here’s tips on how to use it:

git push [remote] [branch]

Push a specified branch, its commits, and any attached objects. Creates a brand new local branch in goal distant repo.

git push [remote] --all

Push all local branches to a selected distant repo.

git branch

Create, edit, and take away branches in git with the git branch command.

Use the branch command in these ways:

git branch [branch]

This creates a brand new branch, which you’ll be able to name by replacing the word in brackets.

git branch -c

This command copies a Git branch.

git push [remote repo] --delete [ branch name]

Delete a distant Git branch, named within the last set of brackets.

git checkout

Use the git checkout command to navigate among the many branches contained in the repo you’re working in.

git checkout [branch name]

Switch to a distinct Git branch, named throughout the brackets.

git checkout -b [new-branch]

Concurrently create a brand new branch and navigate to it. This shortcut combines git branch and git checkout [new branch].

git distant

With the git distant command you’ll be able to see, create, and delete distant connections, “bookmarks” in a way, to other repos. This will provide help to reference repos in your code without having to go find them and use their full, sometimes inconvenient names.

Try these distant commands:

git distant add [alias] [URL]

Add a distant repository by specifying its link and giving it an alias.

git distant -v

Get an inventory of distant connections, and include the URLs of every.

git revert

git revert undoes changes by making a latest commit that inverses the changes, as specified.

One technique to (rigorously!) use git revert is:

git revert [commit ID]

This can only revert changes related to the precise commit that’s been identified.

git reset

git reset is a more dangerous and potentially everlasting command for undoing commits.

This command should only be utilized in local or private repos to forestall the probabilities of interrupting anyone who’s coding in a distant, public repo. Since it will probably “orphan” commits which will then get deleted in Git’s routine maintenance, there’s an actual probability this command can erase someone’s labor.

This can be a complex command that must be used with discretion, so before trying it for the primary time we strongly recommend reading this Git Reset guide from Bitbucket.

git status

git status provides insights into your working directory (that is where every stored historical version lives) and staging area (sort of just like the “under construction” area between the directory and repository). With this command you’ll be able to see where your files stand.

There’s one primary technique to use this command:

git status

See an inventory of staged, unstaged, and untracked files.

git clone

Use git clone to create a duplicate of an existing repository. This is helpful for creating a reproduction of a repo through which you’ll be able to mess around without damaging anything that’s live to the general public.

Listed below are some options for using this command:

git clone [repository URL] --branch [branch name]

Clone the linked repository, then jump right to a selected branch inside it.

git clone [repo] [directory]

Clone a selected repository into a selected directory folder in your local machine.

git init

Use the git init command to create a brand new Git repository as a .git subdirectory in your current working directory. It’s different from git clone as it will probably create a brand new repository as a substitute of only copying an existing one.

Essentially the most common applications of this command include:

git init

Where all of it starts, this transforms your current directory right into a Git repository.

git init [directory]

With this, you’ll be able to turn a selected directory right into a Git repository.

git init --bare

This generates a brand new bare repository, from which commits can’t be made. This creates a helpful staging ground for collaboration.

git rebase

git rebase has history rewriting powers that help keep your commits neat and clean.

It’s an option when you have to integrate updates into the most important branch with a fast-forward merge that shows a linear history.

git rebase [target branch name]

Rebase your checked out branch onto a selected goal branch.

git rebase [target branch name] -i

Initiate an interactive rebase out of your checked out branch onto a distinct goal branch.

That is one other complex command that shouldn’t be utilized in a public repo as it could remove essential elements of the project history. To learn more about how each the usual and interactive versions of this command work, we again recommend Bitbucket and their git rebase guide.

git diff

“Diffing” is the practice of displaying the variations between two data sets.

The git diff command shows variances between Git data sources corresponding to comments, files, etc.

Options for using this command include:

git diff --staged

Shows the difference between what’s staged but isn’t yet committed.

git diff [commit ID 1] [commit ID 2]

This command compares changes between two different commits.

git tag

The git tag command points at a time in Git history, often a version release. Tags don’t change like branches do.

git tag [tag name]

Use this to call a tag and capture the state of the repo on the time.

git tag -d [tag name]

Wish to remove that tag? Run this command.

git rm

The git rm command removes files from each staging and the working directory.

Listed below are a couple of ways to check out git rm:

git rm [file]

That is the essential code to get a file ready for deletion in the subsequent commit.

git rm --cached

This removes a file from the staging area, but keeps it within the working directory so you continue to have a neighborhood copy in case you wish it.

git log

git log provides a, well, log of all of the commits within the history of a repository.

Able to try it out? Here we go:

git log [SHA]

A Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) is a novel identifier for every commit. Use this command to display a certain commit in addition to every other commit made previously.

git log --stat

The command displays which files were modified with each commit, variety of lines added/removed, and variety of files and features edited.

git show

This git show command line provides details on different Git objects like trees, tags, and commits.

Listed below are a couple of ways to exercise this command:

git show [SHA]

The only of git show commands, Use the SHA that we just learned about above to point out the main points of any object.

git show [SHA]:path/to/file

This can show a selected version of a file you’re searching for if you include its SHA.

Still learning tips on how to use Git, have any questions on the above commands, or simply itching to dive into much more variations which you can use to govern your code in 1000’s of how?

We’ve got to shout out the Git tutorials from Bitbucket as an amazing, deep, and interconnected resource that may take you most places you must go together with Git.

And go it is best to. In any case, open-source, and the Git tech that powers most of it, is the longer term of business.

Commands In Real Life: How To Develop On WordPress Using Git + GitHub

We just threw a ton of possibly latest terms and tricks at you.

Should you aren’t deep into Git, it will probably be hard to see how these can all come together to work in a real-life scenario.

So we’ll top things off with a walkthrough of tips on how to use Git and GitHub to set yourself as much as develop on a WordPress website.

1. Install WordPress.org

First up, the WordPress part.

You’re going to install a WordPress.org instance (learn the difference between WordPress.com & WordPress.org in the event you’re not familiar) and create a neighborhood staging environment in your computer.

Should you don’t have already got an amazing process for this, we like Local’s WP-specific dev tool.

2. Install Git

And similar to that, it’s time for the Git part.

Install Git in the event you haven’t already. Find the most recent version on the Git website.

Many Mac and Linux machines have already got Git installed. Check yours by opening your command line interface (like Terminal on Mac or Git Bash on Windows) and entering the primary command of this tutorial:

git --version

If Git is there, you’ll get a version number back. If not, this Git installation guide will get you in your way.

3. Create A Local Repo With Git

Now, we’ll create your local Git repo.

Access your WordPress theme’s folder (this instance includes Twenty Twenty-One) using this command:

cd/Users/[you]/Documents/Web sites/[website]/wp-content/themes/twentytwentyone

Replace [you] and [website] together with your own folder names. Then, initialize this directory as a repository with this command:

git init

So as to add every file within the folder to the index, type in:

git add

Commit your changes with a notation that may keep your history organized with this command:

git commit -m “first commit"

Your local repo is configured!

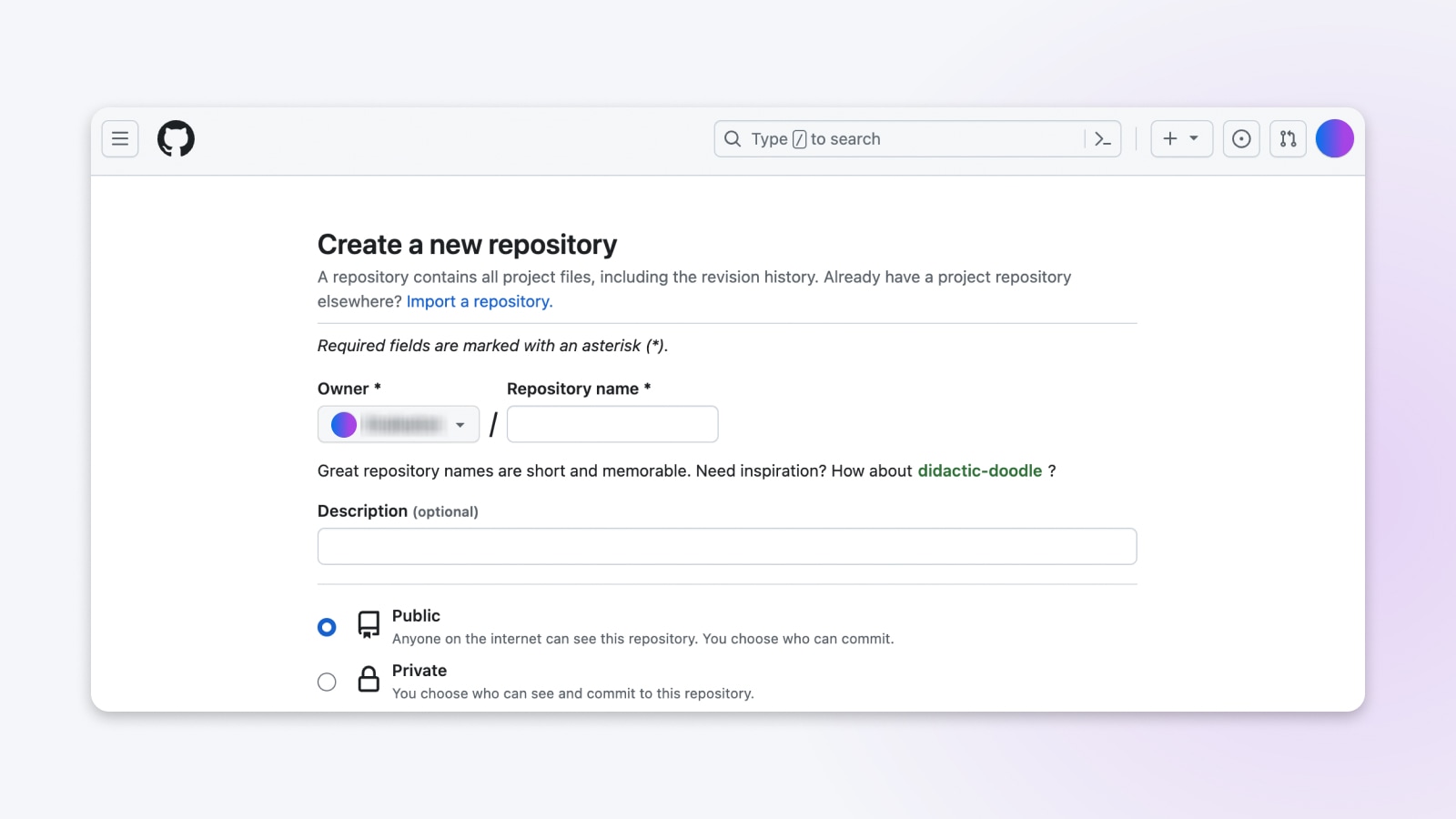

4. Create A Distant Repo With GitHub

At this point, you must create a GitHub account in the event you don’t have already got one.

Once created and signed in, you’ll be able to create a distant repository out of your GitHub dashboard.

If you’re finished following the steps to establish your latest project, it’s time to get your WordPress theme into your latest distant repo in GitHub.

5. Add WordPress Project To GitHub (Learning To Push)

Use these commands in Git to push your WordPress theme into GitHub:

git distant add origin [repo URL]

git push -u origin master

Replace the URL in brackets with a link to the repository you only arrange in GitHub.

Next, you’ll be asked to enter your GitHub username and password.

Once those are in, files committed to your local repo to date can be pushed to your GitHub repo.

6. Optional: Fetch (AKA Pull) Updates

Now that you simply’ve pushed changes out of your local repo to the distant repo on GitHub, the last item to learn is tips on how to pull changes so you’ll be able to do the reverse — add updates from the distant repo to your local one.

After all, in the event you’re working independently on a coding project, you won’t need to do that step. Nonetheless, it’s helpful to know because it immediately becomes mandatory when you’re collaborating with a team who’re all making and pushing updates.

So, we’re going to drag updates into local using the fetch command:

git fetch [URL]

Don’t forget to interchange [URL] with the link to the repository from which you’re pulling.

With that, changes are pulled from GitHub and copied to your local, so each repos are the identical. You’re synced and able to work on the most recent version of the project!

Still need a hand with Git?

For a rather more detailed walkthrough of the above process, try our full guide on How you can Use GitHub for WordPress Development.

Or, higher yet, engage our development experts at DreamHost.

Allow us to handle one-off website tweaks to full-on website management, so your team can get back to the event and management work that moves what you are promoting forward.